Code

import h5py

import numpy as np

import tensorflow as tf

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from tensorflow.python.framework.ops import EagerTensor

from tensorflow.python.ops.resource_variable_ops import ResourceVariable

import timeUp until now, you’ve always used Numpy to build neural networks, but this week you’ll explore a deep learning framework that allows you to build neural networks more easily. Machine learning frameworks like TensorFlow, PaddlePaddle, Torch, Caffe, Keras, and many others can speed up your machine learning development significantly. TensorFlow 2.3 has made significant improvements over its predecessor, some of which you’ll encounter and implement here!

By the end of this notebook, you’ll be able to do the following in TensorFlow 2.3:

tf.Variable to modify the state of a variableProgramming frameworks like TensorFlow not only cut down on time spent coding, but can also perform optimizations that speed up the code itself.

You will be using v2.3 for this assignment, for maximum speed and efficiency.

The beauty of TensorFlow 2 is in its simplicity. Basically, all you need to do is implement forward propagation through a computational graph. TensorFlow will compute the derivatives for you, by moving backwards through the graph recorded with GradientTape. All that’s left for you to do then is specify the cost function and optimizer you want to use!

When writing a TensorFlow program, the main object to get used and transformed is the tf.Tensor. These tensors are the TensorFlow equivalent of Numpy arrays, i.e. multidimensional arrays of a given data type that also contain information about the computational graph.

Below, you’ll use tf.Variable to store the state of your variables. Variables can only be created once as its initial value defines the variable shape and type. Additionally, the dtype arg in tf.Variable can be set to allow data to be converted to that type. But if none is specified, either the datatype will be kept if the initial value is a Tensor, or convert_to_tensor will decide. It’s generally best for you to specify directly, so nothing breaks!

Here you’ll call the TensorFlow dataset created on a HDF5 file, which you can use in place of a Numpy array to store your datasets. You can think of this as a TensorFlow data generator!

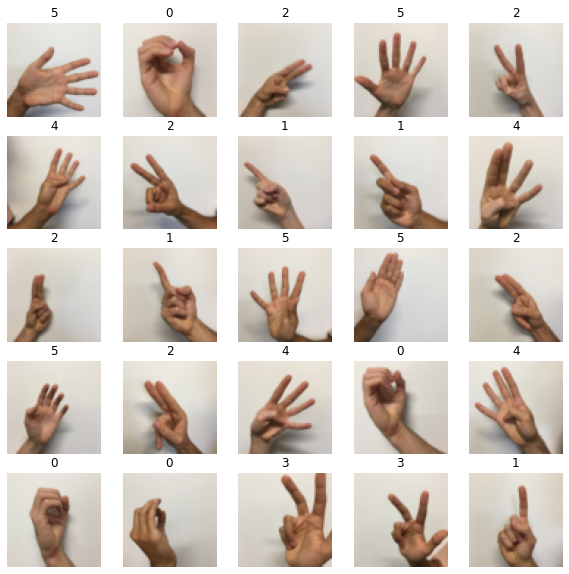

You will use the Hand sign data set, that is composed of images with shape 64x64x3.

Since TensorFlow Datasets are generators, you can’t access directly the contents unless you iterate over them in a for loop, or by explicitly creating a Python iterator using iter and consuming its elements using next. Also, you can inspect the shape and dtype of each element using the element_spec attribute.

tf.Tensor(

[[[227 220 214]

[227 221 215]

[227 222 215]

...

[232 230 224]

[231 229 222]

[230 229 221]]

[[227 221 214]

[227 221 215]

[228 221 215]

...

[232 230 224]

[231 229 222]

[231 229 221]]

[[227 221 214]

[227 221 214]

[227 221 215]

...

[232 230 224]

[231 229 223]

[230 229 221]]

...

[[119 81 51]

[124 85 55]

[127 87 58]

...

[210 211 211]

[211 212 210]

[210 211 210]]

[[119 79 51]

[124 84 55]

[126 85 56]

...

[210 211 210]

[210 211 210]

[209 210 209]]

[[119 81 51]

[123 83 55]

[122 82 54]

...

[209 210 210]

[209 210 209]

[208 209 209]]], shape=(64, 64, 3), dtype=uint8)The dataset that you’ll be using during this assignment is a subset of the sign language digits. It contains six different classes representing the digits from 0 to 5.

{0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5}You can see some of the images in the dataset by running the following cell.

There’s one more additional difference between TensorFlow datasets and Numpy arrays: If you need to transform one, you would invoke the map method to apply the function passed as an argument to each of the elements.

tf.Tensor([0.8901961 0.8627451 0.8392157 ... 0.8156863 0.81960785 0.81960785], shape=(12288,), dtype=float32)Let’s begin this programming exercise by computing the following equation: \(Y = WX + b\), where \(W\) and \(X\) are random matrices and b is a random vector.

Compute \(WX + b\) where \(W, X\), and \(b\) are drawn from a random normal distribution. W is of shape (4, 3), X is (3,1) and b is (4,1). As an example, this is how to define a constant X with the shape (3,1):

Note that the difference between tf.constant and tf.Variable is that you can modify the state of a tf.Variable but cannot change the state of a tf.constant.

You might find the following functions helpful: - tf.matmul(…, …) to do a matrix multiplication - tf.add(…, …) to do an addition - np.random.randn(…) to initialize randomly

def linear_function():

"""

Implements a linear function:

Initializes X to be a random tensor of shape (3,1)

Initializes W to be a random tensor of shape (4,3)

Initializes b to be a random tensor of shape (4,1)

Returns:

result -- Y = WX + b

"""

np.random.seed(1)

"""

Note, to ensure that the "random" numbers generated match the expected results,

please create the variables in the order given in the starting code below.

(Do not re-arrange the order).

"""

X = tf.constant(np.random.randn(3,1), name = 'X')

W = tf.constant(np.random.randn(4,3), name = 'W')

b = tf.constant(np.random.randn(4,1), name = 'b')

Y = tf.add(tf.matmul(W, X), b)

return Ytf.Tensor(

[[-2.15657382]

[ 2.95891446]

[-1.08926781]

[-0.84538042]], shape=(4, 1), dtype=float64)

All test passedAmazing! You just implemented a linear function. TensorFlow offers a variety of commonly used neural network functions like tf.sigmoid and tf.softmax.

For this exercise, compute the sigmoid of z.

In this exercise, you will: Cast your tensor to type float32 using tf.cast, then compute the sigmoid using tf.keras.activations.sigmoid.

Implement the sigmoid function below. You should use the following:

tf.cast("...", tf.float32)tf.keras.activations.sigmoid("...")def sigmoid(z):

"""

Computes the sigmoid of z

Arguments:

z -- input value, scalar or vector

Returns:

a -- (tf.float32) the sigmoid of z

"""

# tf.keras.activations.sigmoid requires float16, float32, float64, complex64, or complex128.

z = tf.cast(z, tf.float32)

a = tf.keras.activations.sigmoid(z)

return aresult = sigmoid(-1)

print ("type: " + str(type(result)))

print ("dtype: " + str(result.dtype))

print ("sigmoid(-1) = " + str(result))

print ("sigmoid(0) = " + str(sigmoid(0.0)))

print ("sigmoid(12) = " + str(sigmoid(12)))

def sigmoid_test(target):

result = target(0)

assert(type(result) == EagerTensor)

assert (result.dtype == tf.float32)

assert sigmoid(0) == 0.5, "Error"

assert sigmoid(-1) == 0.26894143, "Error"

assert sigmoid(12) == 0.9999939, "Error"

print("\033[92mAll test passed")

sigmoid_test(sigmoid)type: <class 'tensorflow.python.framework.ops.EagerTensor'>

dtype: <dtype: 'float32'>

sigmoid(-1) = tf.Tensor(0.26894143, shape=(), dtype=float32)

sigmoid(0) = tf.Tensor(0.5, shape=(), dtype=float32)

sigmoid(12) = tf.Tensor(0.9999939, shape=(), dtype=float32)

All test passedMany times in deep learning you will have a \(Y\) vector with numbers ranging from \(0\) to \(C-1\), where \(C\) is the number of classes. If \(C\) is for example 4, then you might have the following y vector which you will need to convert like this:

This is called “one hot” encoding, because in the converted representation, exactly one element of each column is “hot” (meaning set to 1). To do this conversion in numpy, you might have to write a few lines of code. In TensorFlow, you can use one line of code:

axis=0 indicates the new axis is created at dimension 0

Implement the function below to take one label and the total number of classes \(C\), and return the one hot encoding in a column wise matrix. Use tf.one_hot() to do this, and tf.reshape() to reshape your one hot tensor!

tf.reshape(tensor, shape)def one_hot_matrix(label, C=6):

"""

Computes the one hot encoding for a single label

Arguments:

label -- (int) Categorical labels

C -- (int) Number of different classes that label can take

Returns:

one_hot -- tf.Tensor A single-column matrix with the one hot encoding.

"""

one_hot = tf.reshape(tf.one_hot(label, C, axis=0), (C,))

return one_hotdef one_hot_matrix_test(target):

label = tf.constant(1)

C = 4

result = target(label, C)

print("Test 1:",result)

assert result.shape[0] == C, "Use the parameter C"

assert np.allclose(result, [0., 1. ,0., 0.] ), "Wrong output. Use tf.one_hot"

label_2 = [2]

result = target(label_2, C)

print("Test 2:", result)

assert result.shape[0] == C, "Use the parameter C"

assert np.allclose(result, [0., 0. ,1., 0.] ), "Wrong output. Use tf.reshape as instructed"

print("\033[92mAll test passed")

one_hot_matrix_test(one_hot_matrix)Test 1: tf.Tensor([0. 1. 0. 0.], shape=(4,), dtype=float32)

Test 2: tf.Tensor([0. 0. 1. 0.], shape=(4,), dtype=float32)

All test passedNow you’ll initialize a vector of numbers with the Glorot initializer. The function you’ll be calling is tf.keras.initializers.GlorotNormal, which draws samples from a truncated normal distribution centered on 0, with stddev = sqrt(2 / (fan_in + fan_out)), where fan_in is the number of input units and fan_out is the number of output units, both in the weight tensor.

To initialize with zeros or ones you could use tf.zeros() or tf.ones() instead.

Implement the function below to take in a shape and to return an array of numbers using the GlorotNormal initializer.

tf.keras.initializers.GlorotNormal(seed=1)tf.Variable(initializer(shape=())def initialize_parameters():

"""

Initializes parameters to build a neural network with TensorFlow. The shapes are:

W1 : [25, 12288]

b1 : [25, 1]

W2 : [12, 25]

b2 : [12, 1]

W3 : [6, 12]

b3 : [6, 1]

Returns:

parameters -- a dictionary of tensors containing W1, b1, W2, b2, W3, b3

"""

initializer = tf.keras.initializers.GlorotNormal(seed=1)

W1 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(25, 12288)))

b1 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(25, 1)))

W2 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(12, 25)))

b2 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(12, 1)))

W3 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(6, 12)))

b3 = tf.Variable(initializer(shape=(6, 1)))

parameters = {"W1": W1,

"b1": b1,

"W2": W2,

"b2": b2,

"W3": W3,

"b3": b3}

return parametersdef initialize_parameters_test(target):

parameters = target()

values = {"W1": (25, 12288),

"b1": (25, 1),

"W2": (12, 25),

"b2": (12, 1),

"W3": (6, 12),

"b3": (6, 1)}

for key in parameters:

print(f"{key} shape: {tuple(parameters[key].shape)}")

assert type(parameters[key]) == ResourceVariable, "All parameter must be created using tf.Variable"

assert tuple(parameters[key].shape) == values[key], f"{key}: wrong shape"

assert np.abs(np.mean(parameters[key].numpy())) < 0.5, f"{key}: Use the GlorotNormal initializer"

assert np.std(parameters[key].numpy()) > 0 and np.std(parameters[key].numpy()) < 1, f"{key}: Use the GlorotNormal initializer"

print("\033[92mAll test passed")

initialize_parameters_test(initialize_parameters)W1 shape: (25, 12288)

b1 shape: (25, 1)

W2 shape: (12, 25)

b2 shape: (12, 1)

W3 shape: (6, 12)

b3 shape: (6, 1)

All test passedIn this part of the assignment you will build a neural network using TensorFlow. Remember that there are two parts to implementing a TensorFlow model:

Let’s get into it!

One of TensorFlow’s great strengths lies in the fact that you only need to implement the forward propagation function and it will keep track of the operations you did to calculate the back propagation automatically.

Implement the forward_propagation function.

Note Use only the TF API.

You will not apply “softmax” here. You’ll see below, in Exercise 6, how the computation for it can be done internally by TensorFlow.

def forward_propagation(X, parameters):

"""

Implements the forward propagation for the model: LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR

Arguments:

X -- input dataset placeholder, of shape (input size, number of examples)

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", "W2", "b2", "W3", "b3"

the shapes are given in initialize_parameters

Returns:

Z3 -- the output of the last LINEAR unit

"""

# Retrieve the parameters from the dictionary "parameters"

W1 = parameters['W1']

b1 = parameters['b1']

W2 = parameters['W2']

b2 = parameters['b2']

W3 = parameters['W3']

b3 = parameters['b3']

Z1 = tf.math.add(tf.linalg.matmul(W1, X), b1) # Z1 = np.dot(W1, X) + b1

A1 = tf.keras.activations.relu(Z1) # A1 = relu(Z1)

Z2 = tf.math.add(tf.linalg.matmul(W2, A1), b2) # Z2 = np.dot(W2, A1) + b2

A2 = tf.keras.activations.relu(Z2) # A2 = relu(Z2)

Z3 = tf.math.add(tf.linalg.matmul(W3, A2), b3) # Z3 = np.dot(W3, A2) + b3

return Z3def forward_propagation_test(target, examples):

minibatches = examples.batch(2)

parametersk = initialize_parameters()

W1 = parametersk['W1']

b1 = parametersk['b1']

W2 = parametersk['W2']

b2 = parametersk['b2']

W3 = parametersk['W3']

b3 = parametersk['b3']

index = 0

minibatch = list(minibatches)[0]

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

forward_pass = target(tf.transpose(minibatch), parametersk)

print(forward_pass)

fake_cost = tf.reduce_mean(forward_pass - np.ones((6,2)))

assert type(forward_pass) == EagerTensor, "Your output is not a tensor"

assert forward_pass.shape == (6, 2), "Last layer must use W3 and b3"

assert np.allclose(forward_pass,

[[-0.13430887, 0.14086473],

[ 0.21588647, -0.02582335],

[ 0.7059658, 0.6484556 ],

[-1.1260961, -0.9329492 ],

[-0.20181894, -0.3382722 ],

[ 0.9558965, 0.94167566]]), "Output does not match"

index = index + 1

trainable_variables = [W1, b1, W2, b2, W3, b3]

grads = tape.gradient(fake_cost, trainable_variables)

assert not(None in grads), "Wrong gradients. It could be due to the use of tf.Variable whithin forward_propagation"

print("\033[92mAll test passed")

forward_propagation_test(forward_propagation, new_train)tf.Tensor(

[[-0.13430887 0.14086473]

[ 0.21588647 -0.02582335]

[ 0.7059658 0.6484556 ]

[-1.1260961 -0.9329492 ]

[-0.20181894 -0.3382722 ]

[ 0.9558965 0.94167566]], shape=(6, 2), dtype=float32)

All test passedAll you have to do now is define the loss function that you’re going to use. For this case, since we have a classification problem with 6 labels, a categorical cross entropy will work!

You are used to compute the cost value which sums the losses over the whole batch (i.e. all mini-batches) of samples, then divide the sum by the total number of samples. Here, you will achieve this in two steps.

In step 1, the compute_total_loss function will only take care of summing the losses from one mini-batch of samples. Then, as you train the model (in section 3.3) which will call this compute_total_loss function once per mini-batch, step 2 will be done by accumulating the sums from each of the mini-batches, and finishing it with the division by the total number of samples to get the final cost value.

Computing the “total loss” instead of “mean loss” in step 1 can make sure the final cost value to be consistent. For example, if the mini-batch size is 4 but there are just 5 samples in the whole batch, then the last mini-batch is going to have 1 sample only. Considering the 5 samples, losses to be [0, 1, 2, 3, 4] respectively, we know the final cost should be their average which is 2. Adopting the “total loss” approach will get us the same answer. However, the “mean loss” approach will first get us 1.5 and 4 for the two mini-batches, and then finally 2.75 after taking average of them, which is different from the desired result of 2. Therefore, the “total loss” approach is adopted here.

Implement the total loss function below. You will use it to compute the total loss of a batch of samples. With this convenient function, you can sum the losses across many batches, and divide the sum by the total number of samples to get the cost value. - It’s important to note that the “y_pred” and “y_true” inputs of tf.keras.losses.categorical_crossentropy are expected to be of shape (number of examples, num_classes).

tf.reduce_sum does the summation over the examples.

You skipped applying “softmax” in Exercise 5 which will now be taken care by the tf.keras.losses.categorical_crossentropy by setting its parameter from_logits=True (You can read the response by one of our mentors here in the Community for the mathematical reasoning behind it. If you are not part of the Community already, you can do so by going here.)

def compute_total_loss(logits, labels):

"""

Computes the total loss

Arguments:

logits -- output of forward propagation (output of the last LINEAR unit), of shape (6, num_examples)

labels -- "true" labels vector, same shape as Z3

Returns:

total_loss - Tensor of the total loss value

"""

total_loss = tf.reduce_sum(tf.keras.metrics.categorical_crossentropy(tf.transpose(labels),tf.transpose(logits),from_logits=True))

return total_lossdef compute_total_loss_test(target, Y):

pred = tf.constant([[ 2.4048107, 5.0334096 ],

[-0.7921977, -4.1523376 ],

[ 0.9447198, -0.46802214],

[ 1.158121, 3.9810789 ],

[ 4.768706, 2.3220146 ],

[ 6.1481323, 3.909829 ]])

minibatches = Y.batch(2)

for minibatch in minibatches:

result = target(pred, tf.transpose(minibatch))

break

print(result)

assert(type(result) == EagerTensor), "Use the TensorFlow API"

assert (np.abs(result - (0.50722074 + 1.1133534) / 2.0) < 1e-7), "Test does not match. Did you get the reduce sum of your loss functions?"

print("\033[92mAll test passed")

compute_total_loss_test(compute_total_loss, new_y_train )tf.Tensor(0.810287, shape=(), dtype=float32)

All test passedNote: When using sum of losses for gradient computation, it’s important to reduce the learning rate as the size of the mini-batch increases. This ensures that you don’t take large steps towards minimum.

Let’s talk optimizers. You’ll specify the type of optimizer in one line, in this case tf.keras.optimizers.Adam (though you can use others such as SGD), and then call it within the training loop.

Notice the tape.gradient function: this allows you to retrieve the operations recorded for automatic differentiation inside the GradientTape block. Then, calling the optimizer method apply_gradients, will apply the optimizer’s update rules to each trainable parameter. At the end of this assignment, you’ll find some documentation that explains this more in detail, but for now, a simple explanation will do. ;)

Here you should take note of an important extra step that’s been added to the batch training process:

tf.Data.dataset = dataset.prefetch(8)What this does is prevent a memory bottleneck that can occur when reading from disk. prefetch() sets aside some data and keeps it ready for when it’s needed. It does this by creating a source dataset from your input data, applying a transformation to preprocess the data, then iterating over the dataset the specified number of elements at a time. This works because the iteration is streaming, so the data doesn’t need to fit into the memory.

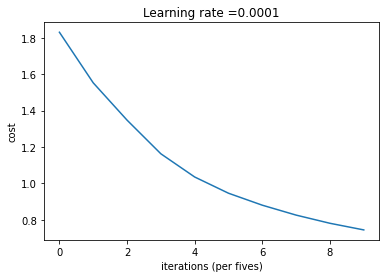

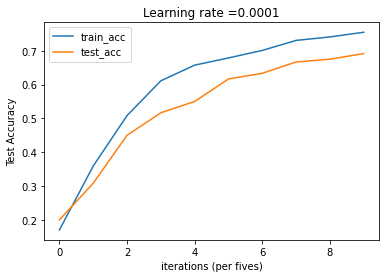

def model(X_train, Y_train, X_test, Y_test, learning_rate = 0.0001,

num_epochs = 1500, minibatch_size = 32, print_cost = True):

"""

Implements a three-layer tensorflow neural network: LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->SOFTMAX.

Arguments:

X_train -- training set, of shape (input size = 12288, number of training examples = 1080)

Y_train -- test set, of shape (output size = 6, number of training examples = 1080)

X_test -- training set, of shape (input size = 12288, number of training examples = 120)

Y_test -- test set, of shape (output size = 6, number of test examples = 120)

learning_rate -- learning rate of the optimization

num_epochs -- number of epochs of the optimization loop

minibatch_size -- size of a minibatch

print_cost -- True to print the cost every 10 epochs

Returns:

parameters -- parameters learnt by the model. They can then be used to predict.

"""

costs = [] # To keep track of the cost

train_acc = []

test_acc = []

# Initialize your parameters

#(1 line)

parameters = initialize_parameters()

W1 = parameters['W1']

b1 = parameters['b1']

W2 = parameters['W2']

b2 = parameters['b2']

W3 = parameters['W3']

b3 = parameters['b3']

optimizer = tf.keras.optimizers.Adam(learning_rate)

# The CategoricalAccuracy will track the accuracy for this multiclass problem

test_accuracy = tf.keras.metrics.CategoricalAccuracy()

train_accuracy = tf.keras.metrics.CategoricalAccuracy()

dataset = tf.data.Dataset.zip((X_train, Y_train))

test_dataset = tf.data.Dataset.zip((X_test, Y_test))

# We can get the number of elements of a dataset using the cardinality method

m = dataset.cardinality().numpy()

minibatches = dataset.batch(minibatch_size).prefetch(8)

test_minibatches = test_dataset.batch(minibatch_size).prefetch(8)

#X_train = X_train.batch(minibatch_size, drop_remainder=True).prefetch(8)# <<< extra step

#Y_train = Y_train.batch(minibatch_size, drop_remainder=True).prefetch(8) # loads memory faster

# Do the training loop

for epoch in range(num_epochs):

epoch_total_loss = 0.

#We need to reset object to start measuring from 0 the accuracy each epoch

train_accuracy.reset_states()

for (minibatch_X, minibatch_Y) in minibatches:

with tf.GradientTape() as tape:

# 1. predict

Z3 = forward_propagation(tf.transpose(minibatch_X), parameters)

# 2. loss

minibatch_total_loss = compute_total_loss(Z3, tf.transpose(minibatch_Y))

# We accumulate the accuracy of all the batches

train_accuracy.update_state(minibatch_Y, tf.transpose(Z3))

trainable_variables = [W1, b1, W2, b2, W3, b3]

grads = tape.gradient(minibatch_total_loss, trainable_variables)

optimizer.apply_gradients(zip(grads, trainable_variables))

epoch_total_loss += minibatch_total_loss

# We divide the epoch total loss over the number of samples

epoch_total_loss /= m

# Print the cost every 10 epochs

if print_cost == True and epoch % 10 == 0:

print ("Cost after epoch %i: %f" % (epoch, epoch_total_loss))

print("Train accuracy:", train_accuracy.result())

# We evaluate the test set every 10 epochs to avoid computational overhead

for (minibatch_X, minibatch_Y) in test_minibatches:

Z3 = forward_propagation(tf.transpose(minibatch_X), parameters)

test_accuracy.update_state(minibatch_Y, tf.transpose(Z3))

print("Test_accuracy:", test_accuracy.result())

costs.append(epoch_total_loss)

train_acc.append(train_accuracy.result())

test_acc.append(test_accuracy.result())

test_accuracy.reset_states()

return parameters, costs, train_acc, test_accCost after epoch 0: 1.830244

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.17037037, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.2, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 10: 1.552390

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.35925925, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.30833334, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 20: 1.347577

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.5083333, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.45, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 30: 1.162699

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6111111, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.51666665, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 40: 1.035301

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6574074, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.55, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 50: 0.946186

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6787037, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6166667, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 60: 0.880409

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.70092595, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6333333, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 70: 0.825984

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.73055553, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.6666667, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 80: 0.781103

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.7407407, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.675, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Cost after epoch 90: 0.744699

Train accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.7546296, shape=(), dtype=float32)

Test_accuracy: tf.Tensor(0.69166666, shape=(), dtype=float32)

# Plot the train accuracy

plt.plot(np.squeeze(train_acc), label='train_acc')

plt.ylabel('Train Accuracy')

plt.xlabel('iterations (per fives)')

plt.title("Learning rate =" + str(0.0001))

# Plot the test accuracy

plt.plot(np.squeeze(test_acc), label='test_acc')

plt.ylabel('Test Accuracy')

plt.xlabel('iterations (per fives)')

plt.title("Learning rate =" + str(0.0001))

plt.legend(loc=0)

plt.show()

Summary

tf.Variable to modify your variablesYou are now able to harness the power of TensorFlow to create cool things, faster. Nice!

Introduction to Gradients and Automatic Differentiation: https://www.tensorflow.org/guide/autodiff

GradientTape documentation: https://www.tensorflow.org/api_docs/python/tf/GradientTape

https://www.coursera.org/learn/deep-neural-network/programming/fuJJY/tensorflow-introduction/lab?path=%2Fnotebooks%2Frelease%2FW3A1%2FTensorflow_introduction.ipynb